Winter Cities

Adaptation to climate change is now an imperative topic in architecture and urban design. Much can be learned from regions where climatic conditions have always been extreme. In such places, not only architecture but also urban design must follow key rules to provide shelter—for example, protection from cold winds and heavy snowfall. Historically, traditional settlements adapted to these conditions out of necessity. But how can modern and contemporary buildings enter into a dialogue of the same kind?

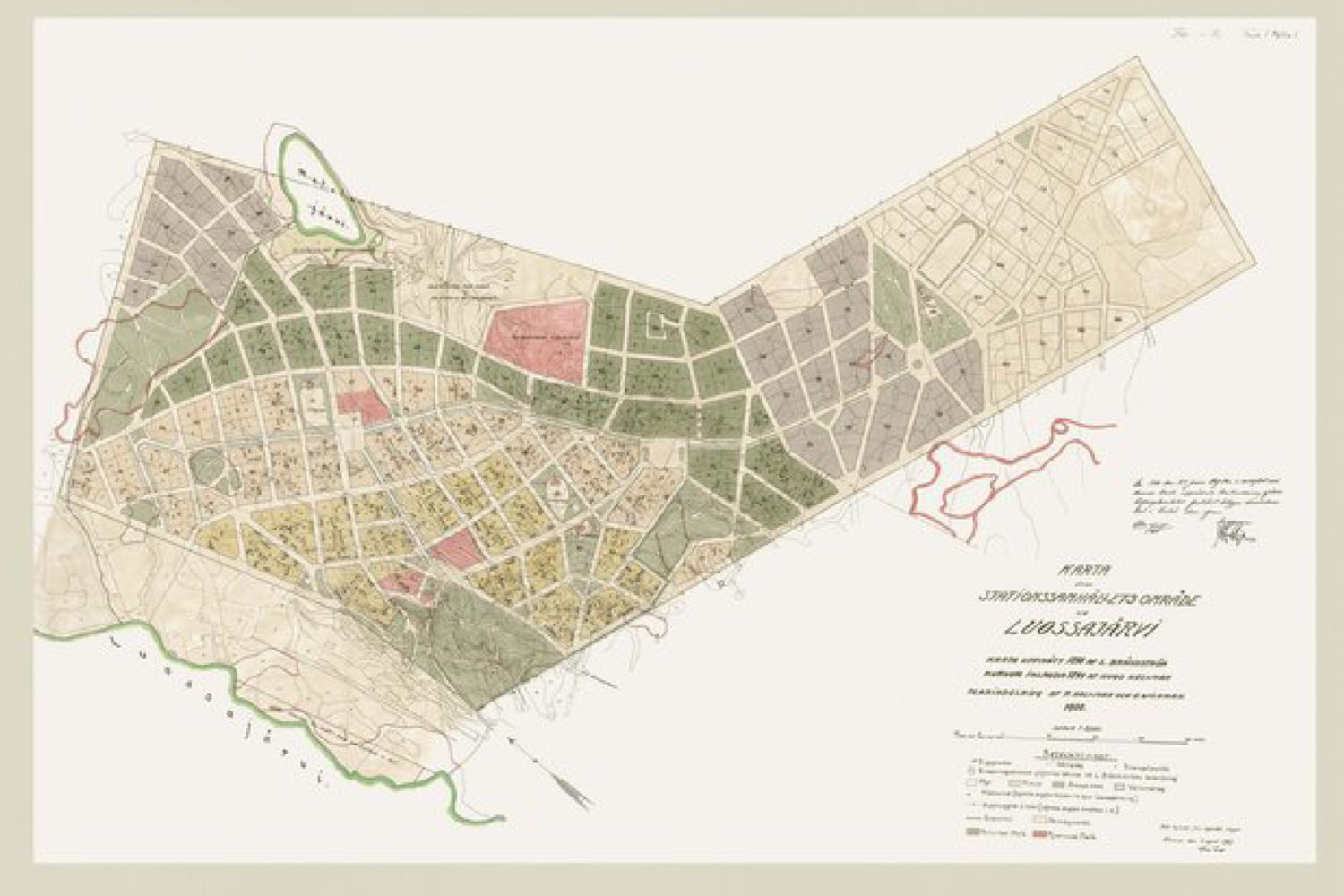

A compelling example can be found in Kiruna, a mining town established in 1900, about 1,200 km north of Stockholm, Sweden. Kiruna is what can be called an Arctic town: winters here are long and intense. Snow typically arrives in late September or October and lasts until May—roughly seven to eight months of snow cover each year. The original town center, founded in the early 20th century, was strategically located on the southwest side of Mount Haukivaara, where the microclimate was slightly warmer than in surrounding areas.

Kiruna during the winter season.

Kiruna during the winter season.

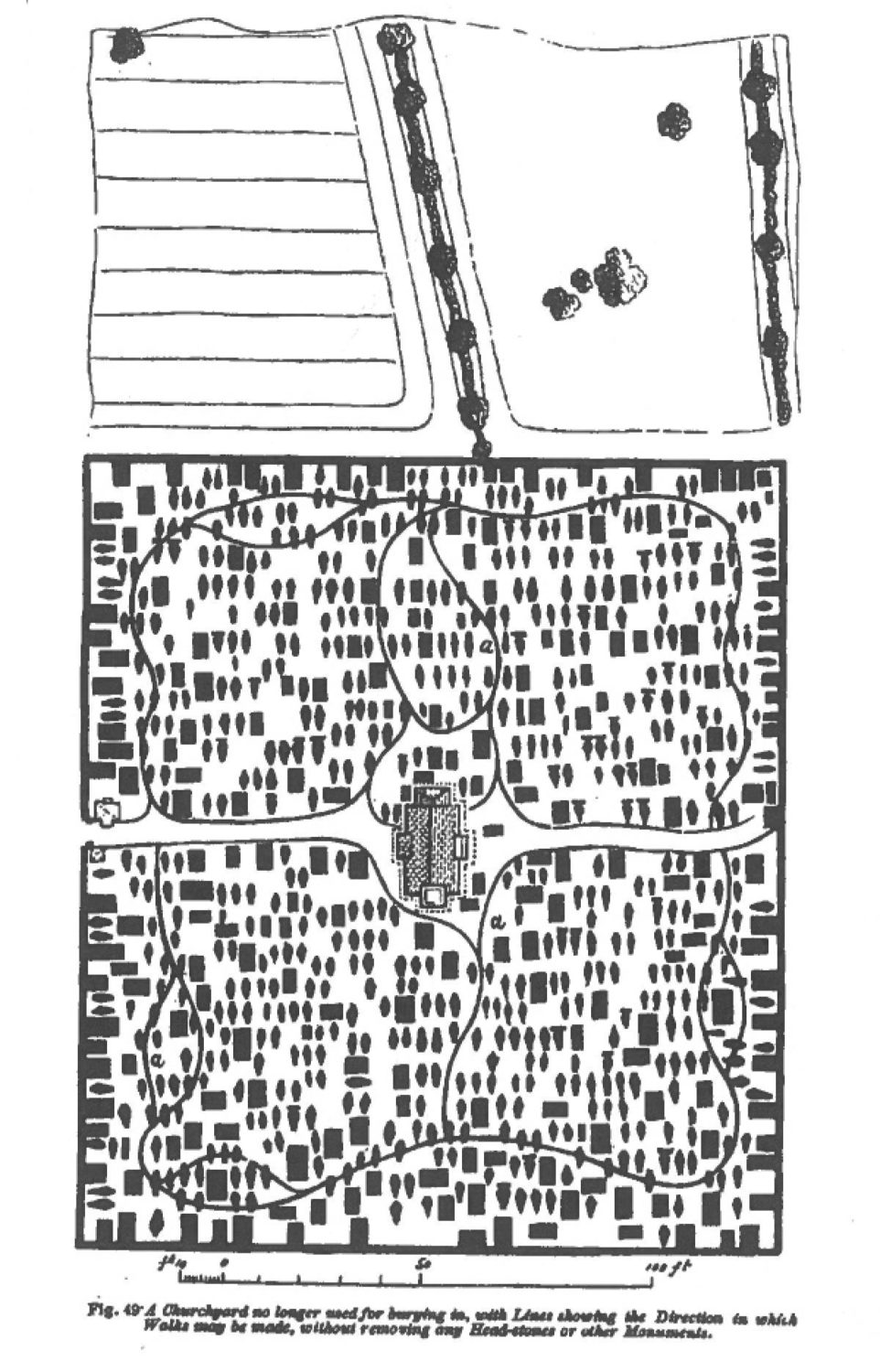

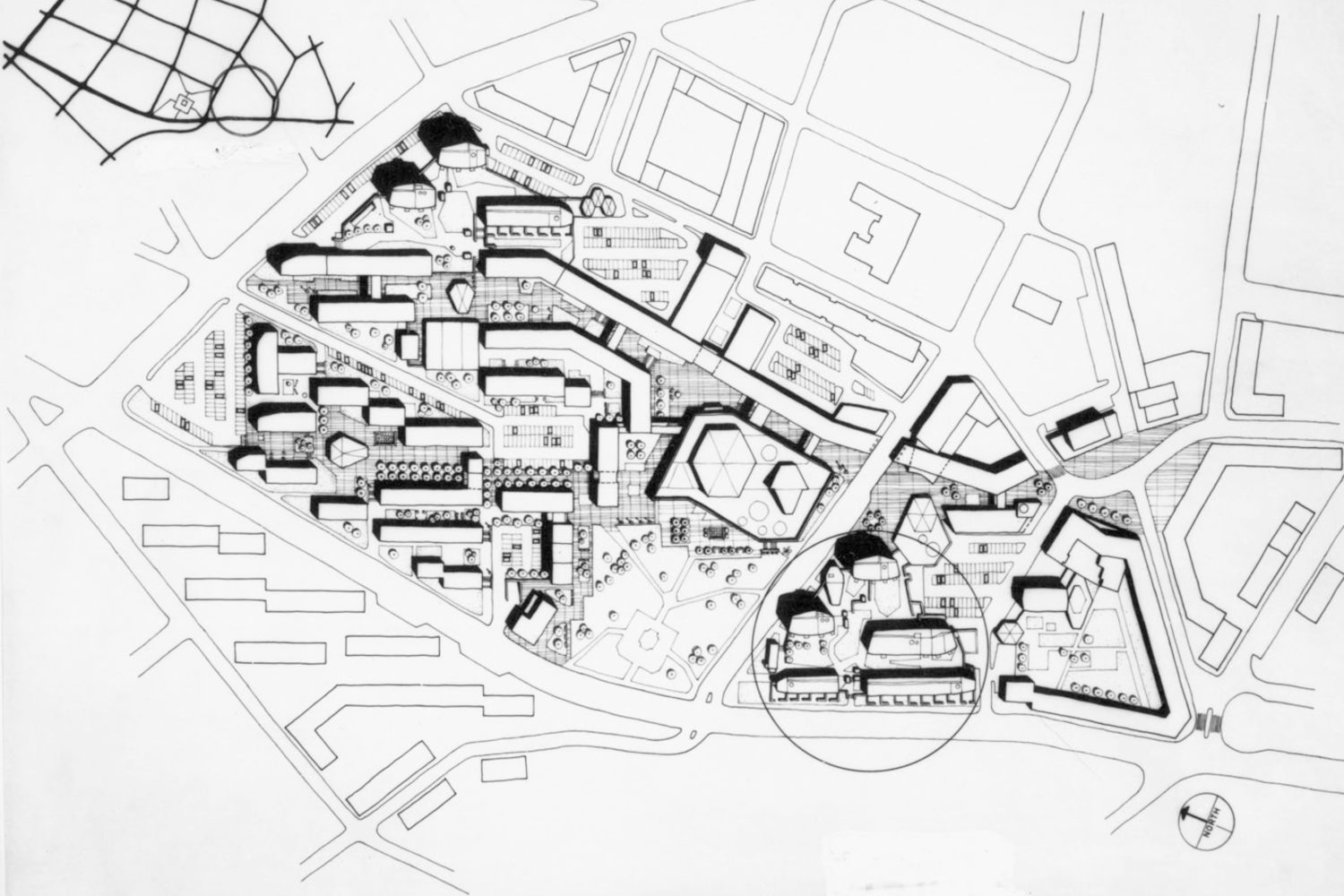

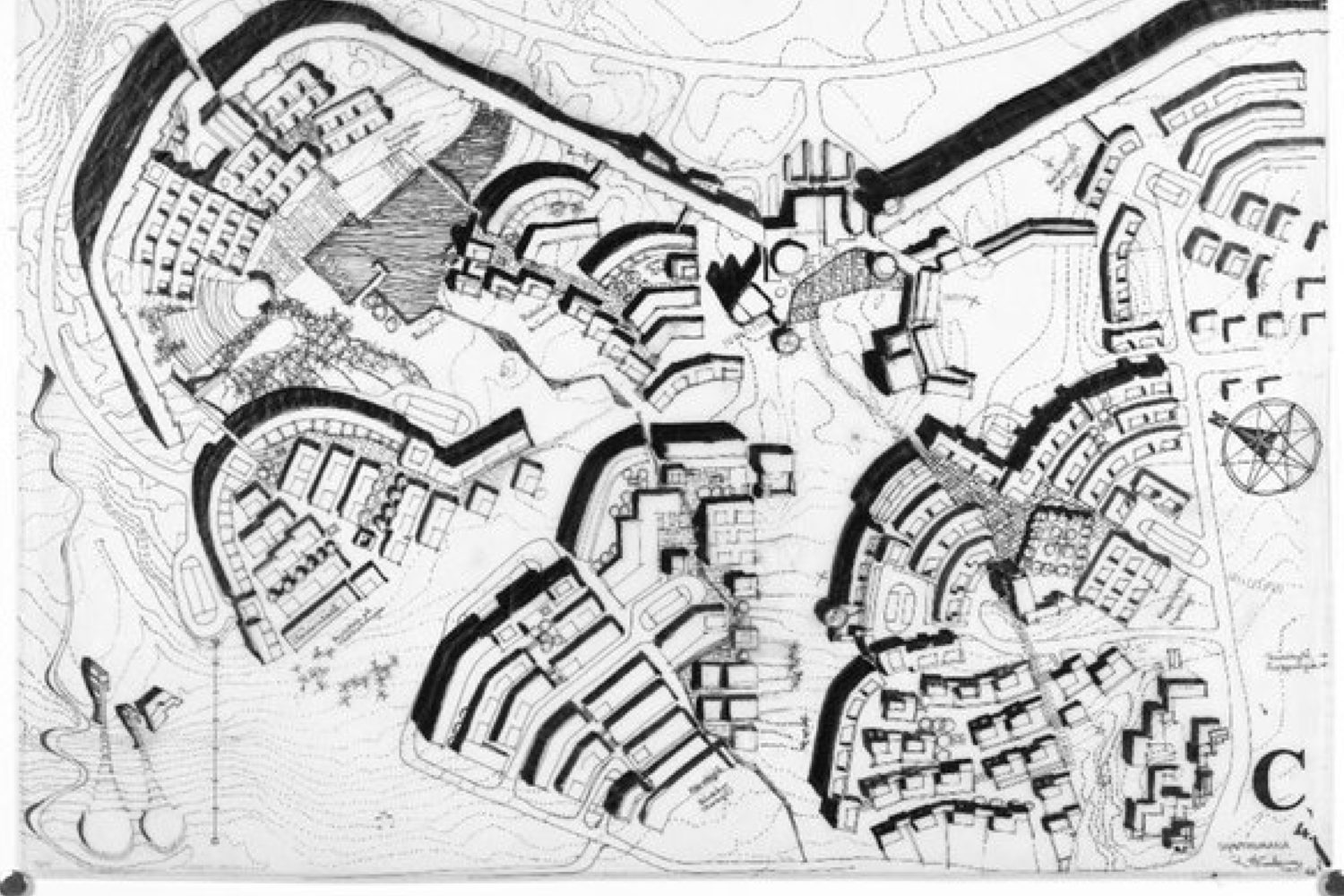

The town was planned by Per Olof Hallman, whose design was strongly influenced by the Garden City movement. The layout was carefully adapted to the natural topography, diverging from the conventional grid structure to preserve scenic views of the surrounding landscape. Instead of a single central square or large park, the plan featured multiple small squares and green spaces strategically placed at street intersections. Streets curved gently rather than running straight, a deliberate strategy to mitigate wind exposure and prevent wind-tunnel effects.

This plan illustrates the role of architecture within broader urban strategy: “Building envelopes are particularly important as they can reduce wind exposure, facilitate snow management, and act as transitional zones between interior and exterior environments." [1]

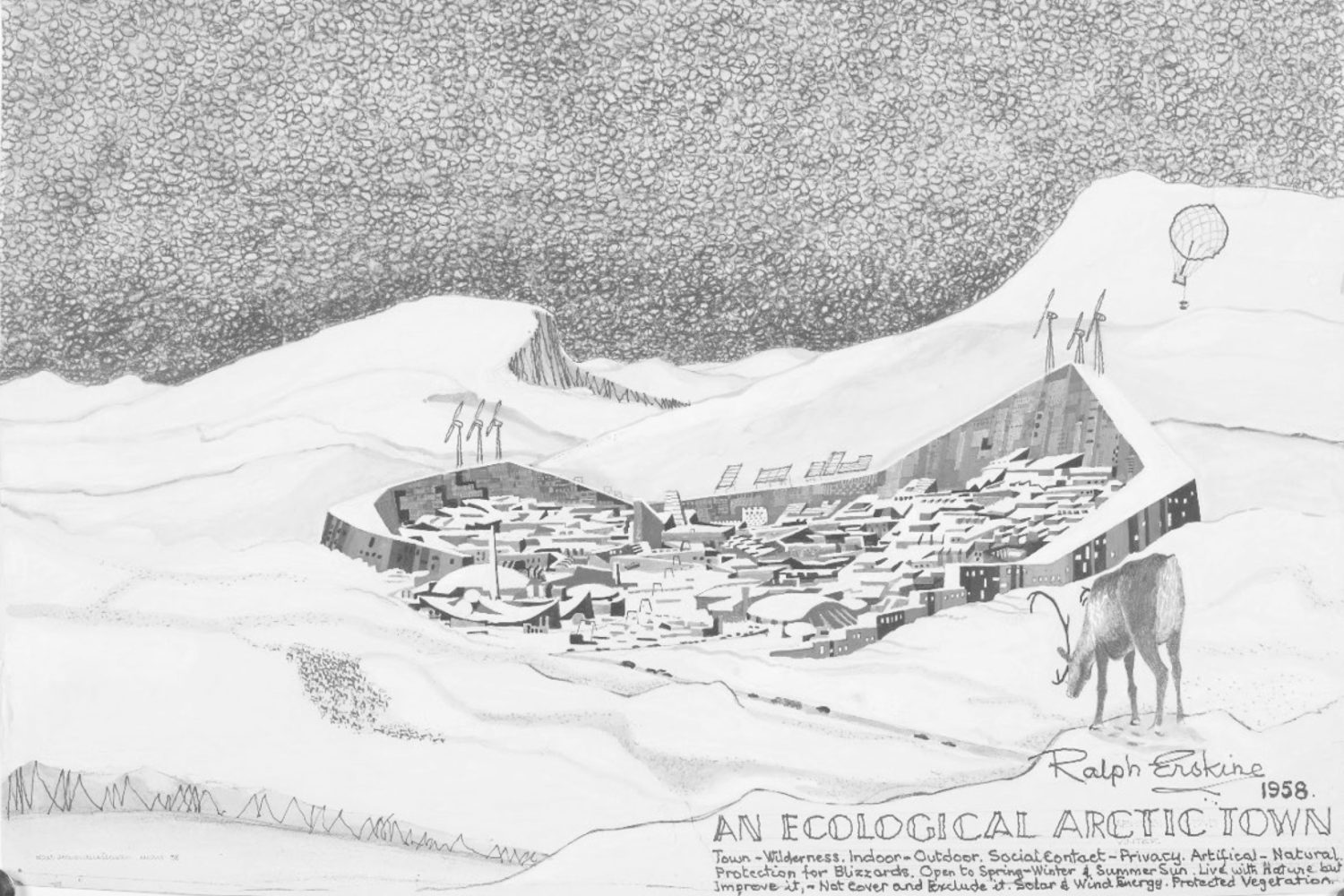

Over time, this approach grew into the Winter Cities movement, advanced by British-Swedish architect Ralph Erskine. A key principle of winter city design Erskine advocated is that it should not “give up” on a relationship with the outdoors by proposing fully heated and enclosed environments.[2] Instead, it seeks to mitigate the harsh effects of winter while fostering a positive relationship between people and their landscape—even at several degrees below zero. This philosophy also informed the recent competition for Kiruna’s new city center, where the brief stated: “The design of the city must facilitate creative use of snow for the creation of functions and added values contributing to Kiruna’s identity and enjoyability." [3]

An especially visionary example is Erskine’s utopian plan for a sustainable Arctic town (1958). It presented a striking image of built form that does not try to dominate its natural surroundings but acknowledges them and responds with design solutions: tall, linear buildings along the perimeter shelter the inner city from prevailing winds, while the overall massing follows the contours of the ground. [4]

This raises broader questions about how we plan our cities today. Often, we oversimplify local climate conditions. In temperate regions, where temperatures are never extremely high or low, climate is treated as a secondary factor in urban planning. But what if we gave greater weight to these forces—even when they are relatively mild (for now)?

What if cities were shaped more by prevailing winds, heat waves, or occasional floods? Would they be changed for the better or for the worse? Could these forces guide density, influence street patterns, or determine the location of community spaces?

[1] Sjöholm, Jennie. (2025). Kiruna: The Arctic town that forgot about winter. URBAN DESIGN International. 1-13. Pg 4

[2] Maudsley, Ann. (2020). North of the Arctic Circle: Ralph Erskine’s Mid-20 the Century Urban Planning and Design Projects in Kiruna and Svappavaara. Pg 60

[3] Kiruna Council. 2012a. Architecture competition brief. A new city centre for Kiruna.

[4] A. Luciani & E. Poma (2023) Sub-Arctic architecture in detail. Erskine’s disappearing architectural and constructional legacy in Kiruna, Journal of Architectural Conservation, 29:3, 275-300

The town plan of Kiruna by Hallman, adopted in 1900

Ralph Erskine. Masterplan for Kiruna city centre, Sweden. Latest completed version, 1957.Circled, the Ortdrivaren quarter.

Ralph Erskine, Svappavaara Centrum (center), 1964.

Ralph Erskine, An Ecological Arctic Town, 1958.